|

|

Bill Porter weaves together historical background, interviews with Zen masters and translations of the earliest known records of Zen in his recent book. |

"Zen masters do not like to talk They either slap you in the face or hand you a cup of tea," says Bill Porter, matter-of-factly. He should know, having lived with, at various times, and studied the practices of Zen monks since 1972.

The idea was reaffirmed when Porter made a journey across the country, from Beijing to Hong Kong, trailing the footprints left by the first six Zen patriarchs - Bodhidharma, Hui Ke, Seng Can, Dao Xin, Hong Ren and Hui Neng - on Chinese spiritual and social life.

The findings went into his most recent book, Zen Baggage: A Pilgrimage to China (Counterpoint, Berkley).

Indeed, by the time Porter was through with the exhausting six-week tour, he had shipped several consignments of tea, gifted to him by Zen monks, back home to the United States, and was still left with more.

As for the famed reticence of Zen practitioners, who believe "to talk about it is to go right by it", Porter did manage to get enough words for a book, but learnt even more by seeing them at work.

Watching the 100-year-old Zen master Ben Huan, who suffered during the "cultural revolution" (1966-76) but became instrumental in the revival of Zen in China, using his calligrapher's brush with a quiet certitude was worth more words than could ever be spoken.

Zen, a special sect of Buddhism that emerged in China in the 7th century, is based on the ideas of experiential wisdom and meditation.

Porter was taken by Zen quite early on. As a graduate student of anthropology in Columbia University, he was meditating with a Chinese Buddhist monk. Soon he decided to chuck school, got his dad to buy a one-way ticket to Taipei and was inducted into the Fo Kwang Shan monastery. That was 1972.

Porter's life has revolved around centers of Buddhist teaching and practice since then. He visited seats of Zen practice, sites where Zen-inspired poets lived and worked, trailing hermits in the misty hills of China.

Although he moved back to the United States in 1999, to settle down in the unruffled and sparsely-peopled Port Townsend in Washington, Zen is too deeply ingrained in Porter's system. It's an inscrutable pull that makes him return to places touched by its aura.

But he has consciously rejected monastic life. After spending about three years in a quieter and less-rigorously academic Buddhist monastery at Hai Ming Temple, a monastery 20 km south of Taipei, when the time came for him to embrace monkhood, Porter ran away.

He was courting his future wife, Ku, whom he had met at the College of Chinese Culture, where he studied Taoism, Chinese art and philosophy. A celibate life minus a drink or two was not what he envisaged for himself. He found a home in a rented cottage atop Taipei's Yang Ming Mountain, near Bamboo Lake.

How Porter adopted the name "Red Pine", began translating the poems of 7th century Zen master Han Shan (Cold Mountain), was turned down by several publishers before being taken under the wings of Buddhist writer-translator John Blofeld, is a story that will survive more retellings.

Lured by the beauty of ancient Zen masters' poems, Porter attempts to get to the bottom of these rather obscure texts. The result? He has become the translator of what is probably the largest collection of ancient Chinese and Sanskrit texts on Buddhism available in English.

As he pored over the works of 14th-century hermit poet Ch'ing Hung (Stonehouse), who described the nuances of hermit life with amazing clarity, Porter realized he had found his feet as a translator.

He translated and edited highly obscure ancient texts, such as the teachings of Lao Tzu, founder of Taoism in the 6th-century BC, and the Diamond Sutra, the oldest known printed book in the world based on the Mahayana school of Buddhist teaching that advocates giving up extreme forms of worldly attachments.

His latest, Zen Baggage, launched recently at The Bookworm in Beijing, seems a natural progression from his earlier work, Road to Heaven: Encounters with Chinese Hermits.

Porter scanned the Zhongnan mountains in central China to locate nuns and monks who might have survived the "cultural revolution" - with amazing results.

"A monk I interviewed in Fujian asked: 'Who's this Chairman Mao (Zedong) you keep talking about?'" The political turmoil failed to touch the life of this monk who had spent more than 50 years in seclusion.

"The basis of Zen practice is self-less community service, which appealed to a lot of Mao's fellow cadres. In fact, it was more Communist than the Communism they advocated."

But at the end of the day, Porter says, life in a Zen monastery is "pretty lackadaisical, you can do pretty much what you want to".

Zen, as Porter points out, is a practice that seems to lend itself to paradoxes, especially now. While Zen practitioners reject words, "no school of Buddhism has generated as much literature. Thousands of books have been written, in the East as well as in the West, about what cannot be expressed by language".

Again, while Zen practice is about a life of quiet contemplation, some of the monasteries, observes Porter, seem to encourage the presence of rather "un-Zen-like" paraphernalia about them. Freshman hermits freely network with the veterans more like a club.

In Zen Baggage, Zen, explains Porter, "is the practice that eliminates the distinction between prajna and dhyana - wisdom and meditation," while the "baggage" - the trappings of life that does not allow one a sense of detachment - "is entirely mine".

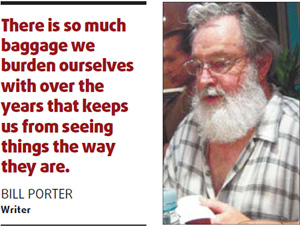

"There is so much baggage we burden ourselves with over the years that keeps us from seeing things the way they are. Some baggage we carry with us for a single thought, some for years and some for lifetimes."

(China Daily July 14, 2009)