Is Chinglish linguistic trash or a cultural treasure?

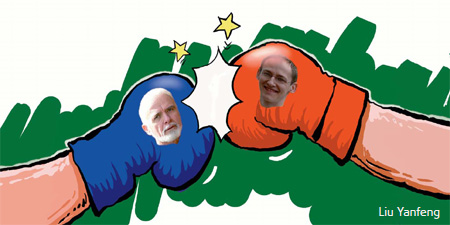

Two academics are going toe to toe over the issue: For American David Tool, it shows nothing but shameful disrespect for English, while German sinologist Oliver Radtke reckons it's an enlightening cultural gem.

"Chinglish should be regarded with pride," says Radtke, who has collected more than 5,000 specimens on his website www.chinglish.de and published two books on the subject. "It's enriching an already-existing language, offering a new point of view, a new set of vocabulary and new usages."

Radtke, who recently applied for what he says is the world's first PhD on the topic of Chinglish, believes the only exception is when mistranslations cause danger, exceptional inconvenience or include the F-word - a common software mistranslation of the character for gan, which also means "dry" or "do".

"If you look at a lot of the Chinese signage examples with those translations, you can see how the Chinese mind is working; it's a window into how Chinese people think," Radtke says.

"My goal is to let Chinglish be considered a bridge between two linguistic and cultural systems."

But while Radtke contends Chinglish adds spice to the alphabet soup that is global English, Tool believes it often adds flies.

Rather than a point of pride, the Beijing Speaks Foreign Languages (BSFL) committee member argues most muddled translations are shameful.

Since 2001, he has helped the Beijing government fix baffling Chinese-English signs and estimates he has so far edited more than 1 million muddled passages.

He has become something of a local luminary for his work, garnering several top accolades, including a spot as the Olympic torch relay's second torchbearer.

Tool says he supports use of some Chinese-English phrases that are at least as clear, and more concise, than "standard English", such as "no nearing", meaning "stay back". But he believes the cultural treasure idea is "basically nonsense". Chinglish, he insists, too often detracts from foreigners' understanding and appreciation of Chinese culture.

"My major interest has always been the cultural aspects. For instance, Chinglish distracts from the dignity and purpose of a museum display when the foolish errors cause foreigners to laugh, or be irritated or confused."

Radtke says Chinglish often works the other way, grabbing foreigners' attention.

"How often do you remember the content of a museum a day after you left it?" he says.

"The whole pedagogical approach is usually pretty dull ... so isn't it great to remember something from that day?"

Radtke adds the Chinese-language information alone is usually vague and rarely contributes more than the Chinglish to visitors' understanding.

He cites the example of a sign for "The former address of the emperor's toilet" at the imperial summer palace in Chengde, Hebei province. The sign's Chinese, he says, is nondescript but visitors are perhaps likelier to remember the spot because of the striking English wording.

Tool, however, recalls watching as garbled Chinglish subtitles made foreign audience members attending a 2001 performance of Monkey Wreaks Havoc in Heaven guffaw so zealously that they disrupted the show.

"I felt the audience was rude to make so much of these errors since the opera house was trying to make the opera understandable to them," says the Beijing International Studies professor.

This experience inspired him to take up his mission of correcting Chinglish in the capital. "I later became much less forgiving of Beijing's opera house managers," he says.

Tool now goes so far as to say he believes incomprehensible Chinglish translations show disrespect for foreigners.

"It is just polite to try to speak or make the signs correct to show common respect for the guests or the folk whose native language it is," he says. "I am not oversensitive; it is just a simple truth, a simple courtesy, as far as I am concerned."

Radtke, though, rates English signage as a weak barometer of Chinese respect for foreigners. "There are more important things, especially in one-on-one interactions with local people, than whether the 'keep off the grass' signs and menus are like what you'd find in New England," he says.

He also points out that bilingual signage is rare in most of Europe.

University of Pennsylvania professor of Chinese language and literature Victor H Mair, who includes Chinglish in class, says foreigners' feelings about Chinese-English are dependant on their knowledge and attitudes about China.

"Many native English speakers who do not know any Chinese can either be insulted or just totally amused by that lack of attention to the basics of English," he says.

"The more Chinese one knows, the more tolerant and even appreciative of Chinglish one usually is, because one understands how and why the Chinglish usages arise."

Tool, who speaks conversational Chinese, nevertheless insists he would feel the same whether his Mandarin was fluent or non existent.

BSFL coordinator Yu Yanni shares the concern about Chinglish as an attention diverter and believes it should be corrected but she doesn't consider it impolite.

"It might distract foreigners, causing them to pay too much attention to the Chinglish and not enough to the exhibitions or anything else," Yu says, stressing that she speaks as an individual rather than for BSFL. "For a general person in China, it may not be easy to tell what standard English is. They make mistakes, but they don't mean any disrespect."

Still, she believes carelessness and thrift are greater culprits than ignorance, especially when it comes to the use of poor translation software.

"Sometimes they suspect the accuracy of the translations but they're too lazy and want to save money," she says.

Translator Zheng Yuantao, who documents Chinglish as a hobby, says part of the problem is that most in his profession are underpaid.

"When you don't offer enough to hire talented people, it's no wonder the Chinglish produced by under-qualified translators and writers is profuse," the Beijinger says.

Chinglish conservation advocate Chen Lijing, who lives in Macao, believes the glut of garbled translations has more to do with average English levels than conscientiousness.

"The usual level of English in the Chinese mainland is not as high as in Hong Kong, Macao, Singapore, Malaysia, etc," she says. "China is coming up on the world stage in various respects, so more and more people in China want to be seen as more international. But the lack of qualified 'language-checking officers' has really created more Chinglish."

Radtke, meanwhile, accepts that some Chinglish arises from a "cha bu duo" - or "more or less" - approach to translation.

"But it'd be very shortsighted to say Chinglish exists because people don't care - that's preposterous," he says. "I smell a certain arrogance behind such an assumption."

Volumes of new mistranslations continue to be produced daily, so Chinglish's future is assured and with it, the scope to amuse - or offend.

(Xinhua June 17, 2009)